Started off Pisces season the right way, at the de Young Museum with my sisters and cousins! I was especially excited to see the exhibit Monet: The Late Years. Additionally, the museum was hosting another collection Gauguin: A Spiritual Journey. Here are some of my favorites, starting with Claude Monet's poignant exhibit.

|

"Water Lilies," ca. 1914-1917. The free little stickers that the museum hands out to visitors featured this particular painting. |

Monet: The Late Years

|

"Water Lilies, Reflections of Tall Grasses," ca. 1897. |

Claude Monet's work towards his later years in life exude such emotion. From losing multiple loved ones, coping with vision loss, and living so close to the conflict of WWI, he had enough reason to stop painting altogether--he even took a self-imposed break!--yet, it was his life's passion and he kept on making art, despite his feelings of despair.

|

"Water Lilies," ca. 1915-1926. This painting was so large, it took up an entire wall. |

|

"Water Lilies," ca. 1914-1915. |

|

"Irises," ca. 1914-1917. |

Admiring the vivid colors of his Impressionist art style, one is drawn to the darkness of his late works although the reason for it is heartbreaking:

It was in 1905 when his perceptions of color began changing. Monet was officially diagnosed with cataracts in 1914, which began clouding his vision. Colors no longer looked brilliant and he couldn't depict shades of light correctly.

Concurrent to this vision impairment, several tragic events seemed to plague Monet one after the other: his second wife, Alice, died in 1911. Then his eldest son, Jean Monet, became sick and died in 1914. That same year World War I began in which both his younger son, Michel Monet, and longtime friend, Georges Clemenceau, served under the French flag.

Concurrent to this vision impairment, several tragic events seemed to plague Monet one after the other: his second wife, Alice, died in 1911. Then his eldest son, Jean Monet, became sick and died in 1914. That same year World War I began in which both his younger son, Michel Monet, and longtime friend, Georges Clemenceau, served under the French flag.

“Nothing in the whole world is of interest to me but my painting and my flowers.”

- remark, shortly after the death of his second wife Alice in 1911

|

"Japanese Bridge," ca. 1899. |

|

"Japanese Bridge," ca. 1918-1924. |

Monet's cataracts resulted in blurred vision and made everything appear in muddy, red-orange colors. His frustrations about this materialized in several unfinished paintings and canvases he'd slashed, torn or ripped before casting aside. Above all, he was strongly determined to keep painting; he memorized the order of pigments on his palette, so he may still paint the colors he was no longer able to perceive.

Also during this time, Monet created stunningly vivid works in red-orange hues which gave his audience insight on how he saw the world through his vision impairment.

Also during this time, Monet created stunningly vivid works in red-orange hues which gave his audience insight on how he saw the world through his vision impairment.

|

"Path Under Rose Arches," ca. 1918-1924. |

|

"Weeping Willow," ca. 1920-1922. His series of weeping willow paintings represent his mourning and sorrow for the fallen French soldiers of WWI. |

“Though I remained insensitive to the subtleties and delicate gradations of colour, my eyes at least did not deceive me when I drew back and looked at the subject in its broad lines, and this was the starting-point of new compositions... Slowly I tried my strength in innumerable rough sketches which convinced me... I could see as clearly as ever when it came to vivid colours isolated in a mass of dark tones. How was I to put this to use? My intentions gradually became clearer... I said to myself, as I made my sketches, that a series of general impressions, captured at the times of day when I had the best chance of seeing correctly, would not be without interest. I waited for the idea to consolidate, for the grouping and composition of the themes to settle themselves in my brain little by little, of their own accord; and the day when I felt I held enough cards to be able to try my luck with a real hope of success, I determined to pass to action, and did so.”

- remark on his 'Water lilies' paintings, between 1900 and 1920

Though his vision kept degrading, the artist delayed medical attention for as long as he could. Concerned over the risks of surgery, he waited until 1923 to undergo it for his right eye only—and was at first devastated by the results despite its success. But once he'd adjusted to his post-op vision, Claude Monet continued to paint up until his death in 1926.

With age may come precarious health issues and the unexpected loss of loved ones... Monet experienced both, as well as life during the Great War. He was able to portray the deep feelings that come with these events onto his canvas, in his signature style of Impressionism. I really enjoyed this exhibit, even though it made me really somber at some points.

Now onto the Paul Gauguin: A Spiritual Journey. Fun fact: this is the first-ever exhibit dedicated to Gauguin shown in San Francisco!

While I recognized one of his famous paintings, I wasn't familiar with the sheer variety and scope of Gauguin's talents, nor I wasn't very knowledgeable of his background and history (professional or personal).

Boy, was I in for a wild ride...

|

"Skaters in Frederiksberg Park," ca. 1884. My cousins and I wondered if Gauguin laughed as he immortalized the person who fell in the ice. |

Growing up, Paul Gauguin didn't received any formal training. He was born in Paris but lived in Peru (linked through his maternal heritage) and lived quite the lavish lifestyle in his childhood, but then moved back to France with his mother and siblings to escape political unrest.

When he was just 19 his mother passed away and one of her close friends Gustave Arosa, a wealthy Spanish businessman and art aficionado, became the legal guardian of Gauguin's younger siblings. It was Arosa's large art collection that sparked Gauguin's passion.

When he was just 19 his mother passed away and one of her close friends Gustave Arosa, a wealthy Spanish businessman and art aficionado, became the legal guardian of Gauguin's younger siblings. It was Arosa's large art collection that sparked Gauguin's passion.

With the help of Arosa, Gauguin became stockbroker in Paris dealing in the art market. During this time he also married his wife Mette-Sophie Gad in 1873, whom he raised five children with in the span of a decade.

In 1874 he found a teacher and mentor in the Impressionist artist Camille Pissaro, who helped Gauguin hone his natural talent. It took only two years until one of Gauguin's paintings was shown in the Paris Salon—the world-famous and renowned government-sponsored exhibit at the Académie des Beaux-Arts.

"It is extraordinary that anyone could put so much mystery into so much brightness,"

- Stéphane Mallarmé after viewing an exhibition of Gauguin's work in November 1893

|

"Portrait of Stéphane Mallarmé," ca. 1891. |

Fate saw that the Parisian market crashed in 1882, leaving Gauguin jobless. He, Mette, and the children moved to her homeland in Denmark. His brief stint as a tarp salesman failed miserably and so Mette became the main provider of their household teaching French.

This became an opportunity for Gauguin in pursuing art as a full-time career, and so he did. The family tried moving back to France in 1883, but it proved unsuccessful and they moved back to Copenhagen. He had stayed in Copenhagen and rural France alone during this period, sending his paintings back home for Mette to sell. However, by 1885 their marriage dissolved completely and Gauguin ultimately left the family for Paris. The last he'd physically see Mette and most of his children in-person was 1891.

|

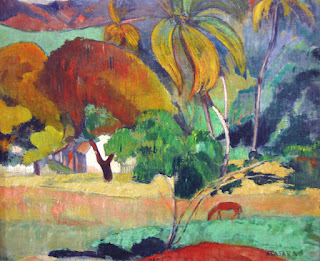

"Landscape from Tahiti," ca. 1893. |

Gauguin's marriage separation was his turning point: he became free to move and act as he pleased. Around 1887 this newfound freedom led him to the exotic and tropical landscapes of Panama, Martinique, and Tahiti.

Here, Gauguin was free to enjoy the pleasures of their indigenous culture. Jobless and without money, he created several beautiful landscapes in his post-Impressionism, Synthesist painting style which focused on the rural lifestyle and the beauty of its people. Not only did he paint, but he also made many wood carvings and ceramics.

|

"Eve and The Serpent," 1889. |

|

"Reclining Tahitian Women," ca. 1894. |

|

"Martinique Woman with Kerchief," ca. 1887-1888. |

Gauguin was free to do what he did because of two things: white supremacy and colonialism. France colonized control over Tahiti and other number of islands, taking resources and land from native people. As all indigenous cultures ravaged by colonization, young girls and women of French Polynesia undoubtedly felt pressured into sex and/or coerced into sex work with wealthy Europeans. In the exhibit, the explanations describing them said it was unknown how willing they really were. As either exploited victims of French colonialism or willing participants in a sexual relationship for economical gain, the circumstances in which Gauguin met and used these women is absolutely atrocious.

“I have a 15-year-old wife who cooks my simple everyday fare and gets down on her back for me whenever I want, all for the modest reward of a frock, worth ten francs, a month.”

- remark that Gauguin, then 48, wrote in a letter to his friend Arman Séguin, in 1897

|

"Woman with Mango Fruits," ca. 1889. |

If his simple philandering doesn't upset you, perhaps knowing that it's been speculated that Gauguin was the one to have sliced off his close friend and fellow painter Vincent van Gogh's ear during a heated argument... although they may have agreed to never reveal the truth out of respect to their past comradery.

Despite all his faults of being an immoral human being, Gauguin's works remain full of wonder and intrigue... for the most part. Once you get past his colonial and white male gaze, his depictions of indigenous women are quite beautiful and stunning. Besides... if art isn't controversial or have an interesting history behind it, is it truly art?

Fitting to the times, the lifestyle he led, and his general character, Paul Gauguin died in 1903—ravaged with syphilis and weakened from alcoholism—from an accidental(?) morphine overdose and a possible heart attack. Karma may have gotten him at the end but at least we have some cool artwork to remember him by.

I highly recommend seeing both of these collections at San Francisco's de Young Museum if you have the opportunity! Monet: The Late Years is available for viewing until May 27th, 2019; The limited-access exhibit, Gauguin: A Spiritual Journey, sells tickets daily and will remain at the de Young until April 7th, 2019.

No comments:

Post a Comment